Crisis Counselling Interventions

There is now extensive literature on the subject of crisis intervention. Starting from the work Lindemann (1944), Caplan (1961), Rapoport (1962) and others, a model of crises has developed together with specific therapeutic methods.

What do we mean by crisis?

Definition of crisis

“A crisis can develop when an event, or series of events takes place in a person’s life and the result is a hazardous situation. It is important to note that the crisis is not the situation itself, rather it is the person’s perception of and response to the situation” (Parad, 1971 p.197)

Description of the crisis process

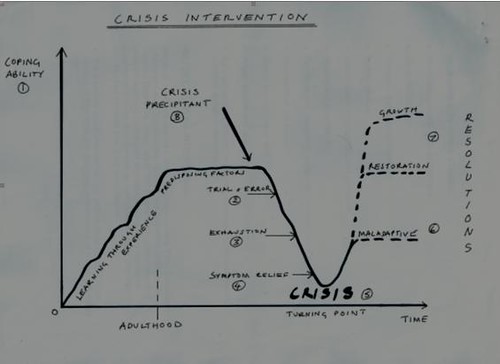

(1) During life, each person develops a repertoire of coping abilities to deal with stress-inducing events. Some of these are beneficent and adaptive, e.g. discussing a problem with appropriate others, or maladaptive, e.g. heavy drinking.

If problems arise for which the person’s normal coping mechanisms are inadequate then stress increases. The person usually resorts to variations of existing coping strategies, and then to (2) “trial and error” methods.

If these fail, a crisis process develops, involving increased levels of anxiety, progressive disorganisation and (3) exhaustion, withdrawal, and a shift of motivation from the solution of the problem itself to seeking immediate relief of (4) the feelings of distress.

The crisis eventually reaches (5) a turning point: either the vulnerability and the stress produces a flight into illness or the other maladaptive defence, or else learning occurs, and the person resolves the crisis in some appropriate way. Crises are self-limiting in time since the demands of relief from distress force some adaptive or maladaptive adjustment.

(6) If the adjustment is maladaptive, the person’s coping ability is reduced, there is less orientation to reality, and independence declines. Unrealistic expectations are made of others, particularly of medical professionals, and the person’s status becomes that of a patient or a client.

(7) If however, adjustment is adaptive, the coping ability will be enhanced, the value of problem-solving attitudes is reinforced, orientation to reality is heightened, and a personal responsibility is accepted.

(8) Research indicates that the event which triggers a crisis may include both major and traumatic ones, and events which are apparently minor. In the latter case, then, it is often the case that there have been significant events in the past twelve months which have decreased the person’s coping ability. It is also clear that certain factors increase a person’s vulnerability to crisis.

Crisis here should be distinguished from furore. Farewell described a state of furore as a kind of re-enactment of emotional components of the crisis, in which discharge of emotional components becomes ritualized. In furore, paradoxically, what looks like a crisis superficially is, in fact, a maladaptive coping mechanism, and professionals, when involved, are used as witnesses and onlookers by the people involved rather than sources of real help.

Defining features of a crisis

- A triggering event or long-term stress

- The individual experiences distress

- There is loss, danger, and/or humiliation

- There is a sense of uncontrollability

- The events feel unexpected

- There is disruption of routine

- The distress continues over time (from about 2 – 6 weeks)

Responses to crisis stress

- Short term unreality and anaesthesia

- Sleep disturbance

- Disrupted appetite and digestion

- Muscle tension

- Aches, pains, skin rashes and infections

- Anxiety and depression

- Problems with reasoning, judgement, concentration and memory

- Avoidance of the problem

- Mental preoccupation with the problem

- Anger, shame and guilt

- Low self-esteem, loss of confidence, depression, flatness, apathy, volatility, agitation and withdrawal

History of crisis intervention

Studies around this began in 1906 at a suicide prevention centre in New York. Developed by Lindemann and Caplan in the 1940s in the aftermath of Boston’s Coconut Grove fire, when nearly 500 people died. Observations were made of delayed reactions, acute grief, reactions leading to no resolution. This developed a concept of working through loss as quickly as possible after the event. This was used further in World war 2 with war victims.

Aims of crisis intervention

To resolve the most pressing problem(s) within an eight to sixteen weeks period.

To reduce immediate fear and danger.

To provide support, hope and alternative ways of coping and growing.

To mobilise previously hidden strengths and capacities.

To avoid maladaptive coping mechanisms, e.g. drink, depression, self-harm, suicide.

To restore equilibrium and reduce unpleasant side effects.

To mobilise internal and external resources.

To integrate experience into person’s other life experiences.

To bolster the person’s new repertoire of coping skills for the future.

One of the most effective ways of doing this is through face to face counselling.

What is special about crisis intervention

- It includes an assessment of risk and mental health

- Confidentiality is essential (limits here apply)

- It is intensive, immediate, flexible, suited to lots of ways of working, short-term and focused

- It is collaborative: agreed objectives and goals between client and therapist

- It offers reassurance and hope of recovery

- It puts an emphasis on strengths

- It is a psychosocial intervention, i.e. people are seen in the context of their lives and histories

- Interventions can be practical too

- It takes into account vulnerabilities, language difficulties, mental health problems, poverty, violence, earlier trauma

Roberts seven stage model

As a service we seek to apply Robert’s seven-stage model and framework for crisis intervention:

- Assess risk and mental health

- Establish rapport and engage the client

- Identify major problems

- Deal with feelings

- Explore alternative coping mechanisms

- Develop an action plan

- Develop a termination and follow up protocol

References

Caplan, G. (1961) An approach to Community Mental Health. Grune and Stratton, New York

Lindemann, E. (1944) Symptomatology and management of acute grief. American Journal of Psychiatry, 101:141-8

Rapoport, L. (1978) The state of crisis: Some Theoretical Considerations. Social Services Review 36. Reprinted in PARAD, H.G. (ed) Crisis Intervention, Family Service Association of America. New York

Find the right counsellor or therapist for you

All therapists are verified professionals